The Halfway Point

February 01, 2020

Learning 3,000 Chinese Characters

You can track my progress here.

I learned 191 new characters, taking my total to 1,560/3,000.

I spent 14 hours learning characters this week.

Here’s how I started learning Chinese and what I’ve learned so far along the way.

Starting Off

I started learning Chinese with Duolingo in late November. It was fun for a few days, but then it got super repetitive and boring. Plus I hate the robot-voice-audio that the app uses.

I was especially struggling to learn the Chinese characters. They all looked like a jumble of lines smashed together, and Duolingo didn’t have explanations for how to write them or learn them in a systematic way.

Progress was slow, and I figured there had to be a better way.

Finding a Better Way to Learn

I started looking for other ways to learn and found this video on Youtube, a presentation that Pablo Roman gave at a language learning conference.

Pablo used something called the Heisig method to learn 2,000 characters in 50 days, a rate of 40 characters/day.

40 characters/day seemed pretty compelling to me. The examples he gave in the video were clear, simple, and easy to remember. It was the first time I could actually remember a character with more than four strokes.

The Heisig method is based on a book written by James W. Heisig. In the book, he breaks down characters into primitive elements and then gives you a creative story to remember each character.

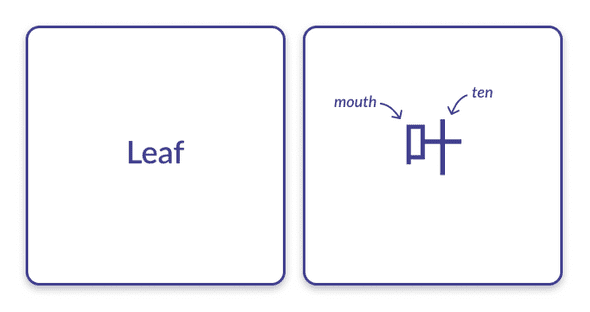

For example, the character for leaf (叶) is made up of the primitives mouth (口) and ten (十). The story for this character talks about how the Chinese are famous for taking leaves and turning them into medicine - no less than ten different types of leaves go into the concoction the doctor is making. However, the doctor forgets to grind them up first and you end up stuffing ten leaves in your mouth.

It seems kind of silly, but it works.

After character #500, the book stops giving you pre-written stories and asks you to come up with your own.

I decided to buy the Heisig book (Learning Simplified Hanzi, James B. Heisig) on iBooks (It’s significantly cheaper than on Amazon) and give it a go.

Also, I’m using Anki (a spaced-repetition-software) to solidify what I learn from the book. Someone created a shared deck with all of the vocabulary from the book, so I just downloaded that instead of adding them manually.

My Goal

My goal is to finish the book (3,000 characters) in 120 days. To do this, I need to learn 25 new words per day. I started December 2, 2019, so that gives me until March 31st.

I’ve now learned over 1,500 characters using this method. It’s been fun, frustrating, challenging, and rewarding. It’s taken me 85.8 hours of studying and 62 days to get this far.

Here’s what I’ve learned during the first half of my journey to 3,000. 👇

Practice Writing Characters on Paper

When I first started, I didn’t physically write out characters.

I tried to just picture them in my mind before I clicked through to reveal the answer. This works for the first few chapters because the characters are all pretty simple (口, 一, 人).

This starts to create a problem when things get more complex.

You start being a little too lenient on yourself when you forget a line. Next, you’re giving yourself credit for characters you got 70% right.

Before you know it, you start forgiving yourself for missing characters that were completely wrong; you tell yourself you just got confused or you ‘actually did know it.’

Your brain is always looking for the easiest way out. To keep yourself honest, prove that you really know a character by writing it out.

Also, writing requires more active engagement, which means more active learning, which means better learning.

Just as your thoughts become clearer and more refined when you write an essay on a topic, characters are sharper in your mind when you physically write them down. Which brings me to my next point…

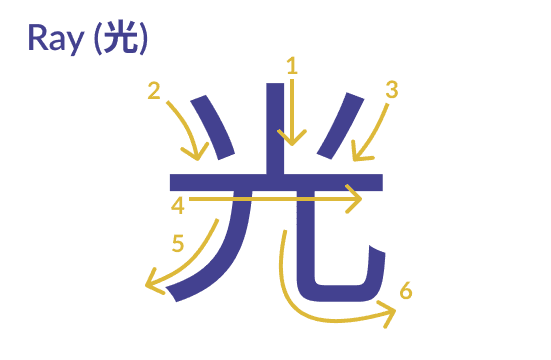

Learn Stroke Order! (It’s not that hard)

Chinese characters are made up of strokes that you need to write in a certain order.

I started off not caring about stroke order. In my mind, I wasn’t ever going to be physically writing characters, so I just assumed I didn’t need to pay attention to it.

I would usually just scribble down the strokes in whatever order they came to me. I guess this is fine for easy characters like mouth (口), but when you get into more complex characters (like 翻), the order of difficulty becomes much greater.

In a weird way, learning the stroke order actually makes it easier to remember the character. The reality is there are a few characters that are super hard to make stories for and you’ll need to rely on rote memorization to master them. For these characters especially, learning the stroke order is a helpful way to solidify the character in your mind.

Plus, there are tons of posts online from people with wayyyyy more experience than me that are encouraging others to not ignore this. It’s really not that hard, and you don’t have to be perfect, but at least try.

Master the Important Characters

Every chapter, there are 3-6 characters or primitives that form the basis for the rest of the characters in the chapter. For example, one of the key characters for chapter 5 is 直, meaning straight. Many characters in the chapter include this element.

If you can get these key characters/primitives down pat, it will make the rest of the lesson much easier. You won’t struggle to remember the same element for every single character. Plus, the important elements are going to come up again and again in later chapters, so it’s worth investing the energy up front to avoid the pain later down the road.

I personally found this to be more of an issue around the 800-900 character point, when the building blocks weren’t as simple or easy to remember as before.

Some primitives can be confusing because they’re so similar to others. For example, you need to have a solid grasp on the primitives* for cliff (厂), cave (广), and illness (疒). Confusing them can cause a lot of frustration and wasted time later on.

* These are not the meanings of the characters, but meanings for primitive elements that Heisig defines.You’ll Never “Just Remember It”

When you come across a character that’s really tough to make a creative story for, don’t get lazy or kid yourself. You’re never going to “just remember this one.”

I did this a few times, and it always came back to bite me. As I mentioned, after character 500, the Heisig book stops including pre-written stories and asks the reader to come up with his or her own. Sometimes, I was feeling lazy and I’d just skip it.

I thought I’d just be able to make those characters stick. Here’s what actually happened:

It worked for that day - I remembered the character for 24 hours after I learned it. But any longer than that and I had forgotten it, flipping back through my notebook to see what story I had written to remember it— only to find that I had skipped that one. Frustrating.

It’s much better to take 3-4 minutes and come up with a good story the first time than to spend 5-20 minutes later reviewing the character repeatedly.

A good lagging indicator of the quality of your mnemonics is the Again count in Anki, which you can find in your stats page. If you’re hitting the Again button too much, you either need to adjust your Anki settings or you need to put more effort into coming up with good stories. I try to get 85% of my answers correct.

Side note: I am currently writing all my stories/mnemonics in a Google Doc and that I’ll release as a PDF once I’m done. I actually don’t think it’s 100% necessary to come up with your own stories as long as the stories are memorable. In my view, what you lose in active engagement from coming up with your own stories is more than compensated for in time saved by not having to create them.

Use Stories as Close in Meaning as Possible

This may seem obvious, but you should try to make your stories and mnemonics tie back to the original keyword as closely as possible. If you are learning the verb mail, make sure your story is describing the act of mailing rather than mail as a noun.

Try to use the first image that comes to your mind.

I kept messing up on the character for short. When you think of the adjective short, you probably think of a person that is short in stature. But the primitive elements in the character made it easier for me to come up with a story about drawing the short stick — still the same meaning! But it was harder for me to remember since it was one degree removed from what you’d normally think of.

Recall, Don’t Recognize

In my class on memory in college, my professor explained how neuroscients break up memory into two different categories: recollection and recognition. Being able to recall something indicates a stronger memory than just being able to recognize something.

Applied to learning characters, recollection is being able to write out the character, while recognition is being able to recognize a character that is presented to you (without being able to produce it completely on your own).

At character 700 or so, I turned off all the hanzi cards in the Anki deck (the ones that prompt you with a Chinese character and ask you to remember the English).

I was already spending 2 hours a day on Anki, and I was drowning in reviews. I knew I had to learn 25 new characters/day, so I couldn’t just stop to clear out the backlog.

Plus, I felt like the Chinese cards were throwing me off. I would see a hanzi card with a character that I could recognize but not recall. I’d answer Good for that card, and because I had recently seen the character, I would answer Good when the card with the English prompt came up, even though I probably wouldn’t have known it had I seen the English first.

That messes up your Anki algorithm and lowers your engagement level, leading to worse long term memory formation.

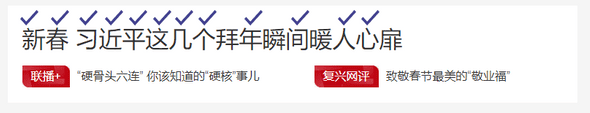

Use a Good Mix of Character Learning and Other Practice

Halfway to my goal, I wish I was able to speak more and read sentences. I can recognize a lot of characters that I see, but I can’t make heads or tails of the sentence I’m trying to read. The other day I looked at the homepage of CCTV (Chinese public news) and could recognize all these characters but couldn’t read the sentence:

I’ve done some practice with Hello Chinese (which is much better than Duolingo… at least, more entertaining), and I wish I could do more. Unfortunately, learning characters takes 1.5-2 hours a day and I’m not able to dedicate more to it.

If I could start over again, I’d probably cut back on the number of characters I’m learning in favor of more traditional language practice (speaking, reading, etc.).

That said, I’m going to stick to my goal of 3,000 because:

- I want to see if I can do it

- I want to see if there are benefits to doing it this way

By learning 3,000 characters, my hope is that I’ll have a much better base that I can use to accelerate my more traditional learning in the future.

That’s all for this week, thanks for reading! If you know anyone who likes to learn languages or is learning Chinese, please consider asking them to subscribe to my newsletter.

I send updates on my progress every Saturday.